By Brant Wilkerson-New

November 17, 2025

Key Takeaways

- Merrill’s Principles of Instruction provide a research-based framework for designing effective experiences centered on real problems.

- The five core principles are: problem-centered learning, activation of prior knowledge, demo of skills, application by learners, and blending into realistic activities.

- Applying these guidelines leads to increased engagement, better retention, and practical application of information and skills.

- Merrill’s philosophy is adaptable to any subject, audience, or delivery method, making them a valuable tool for instructional designers.

- Challenges exist, but with careful planning and a learner-centered approach, Merrill’s Principles of Instruction can transform design and lead to more effective outcomes.

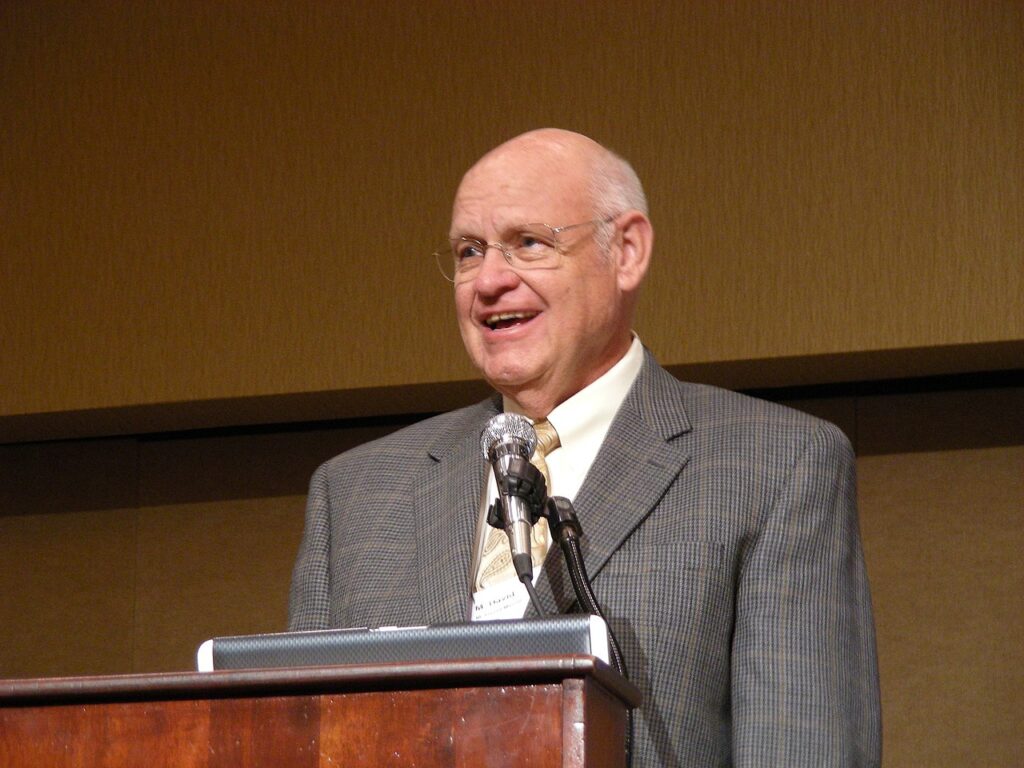

In the ever-evolving landscape of instructional design, educators and designers continually seek models that foster effective learning and real-world application. Among the most influential frameworks is Merrill’s Principles of Instruction, developed by David Merrill. These guidelines offer a research-backed foundation for designing programs that leads to meaningful learning experiences and improved knowledge retention. Whether you are an instructional designer, educator, or organizational leader, understanding and applying Merrill’s principles can transform the way you approach teaching and learning.

What are Merrill’s Principles of Instruction?

Merrill’s Principles of Instruction, often referred to as Merrill’s First Principles, are a set of five core guidelines for designing effective instruction. David Merrill, a renowned educational psychologist, introduced these guidelines after synthesizing decades of research on instructional design theories and models. The goal was to distill the essential elements that make learning truly effective, regardless of the subject matter or delivery method.

At the heart of the philosophy is the belief that learning is promoted when instruction is centered around real-world problems and tasks. The guidelines emphasize active engagement, the use of prior knowledge, demonstration, application, and integrating new information. By following these guidelines, instructional designers can create experiences that not only impart knowledge but also enable learners to apply what they have learned in practical, meaningful ways.

Let’s explore each in detail:

1. Problem-Centered Learning

The first and most fundamental principle is that learning is promoted when learners are engaged in solving real-world problems. Rather than presenting isolated facts or abstract concepts, Merrill’s model encourages teaching that begins with a realistic task or problem. This approach provides context and relevance, motivating learners to engage deeply with the material.

For example, instead of teaching mathematical formulas in isolation, an instructor might present a scenario where learners must use those formulas to solve a budgeting problem. This context helps learners see the value of what they are learning and encourages them to apply their knowledge and skills.

2. Activation of Prior Knowledge

The second principle states that learning is enhanced when teaching activates existing knowledge. Before introducing new information, effective instruction prompts learners to recall or reflect on what they already know. This activation creates a mental framework for integrating new concepts.

Instructional designers can implement this principle by asking learners to share experiences, answer questions, or complete activities that relate to the upcoming content. For instance, before teaching a new software tool, an instructor might ask learners to discuss similar tools they have used in the past. This process not only prepares learners for new information but also helps them make connections between old and new information.

3. Demo of Skills

According to Merrill’s third principle, learning is promoted when new information and skills are demonstrated to the learner. Demonstrations provide concrete examples and models for learners to observe, making abstract concepts more tangible and understandable.

Effective demonstrations can take many forms, including live instruction, video tutorials, simulations, or role play. The key is to show learners how to perform a task or apply a concept before asking them to do it themselves. For example, a science teacher might conduct an experiment in front of the class, highlighting each step and explaining the reasoning behind it. This demonstration helps learners visualize the process and understand the underlying principles.

4. Application by Learners

The fourth principle emphasizes that learning is promoted when learners are required to apply new knowledge and skills. After observing demonstrations, learners should have opportunities to practice and receive feedback. This hands-on application solidifies learning and allows learners to test their understanding in a safe environment.

Instructional designers can facilitate application through exercises, simulations, case studies, or real projects. For example, after education on customer service techniques, learners might participate in role-playing scenarios to practice their skills. Immediate feedback from instructors or peers helps learners refine their approach and deepen their understanding.

5. Integrating into Real-World Activities

The final principle asserts that learning is promoted when new knowledge is integrated into the learner’s world. Integration involves encouraging learners to reflect on, discuss, and use new knowledge in real contexts. This step ensures that knowledge does not remain theoretical but becomes part of the learner’s everyday life and work.

Instructional designers can support incorporating it by assigning projects that require learners to apply their skills outside the classroom, facilitating group discussions, or encouraging learners to teach others. For example, after completing a training program, employees might be asked to implement new procedures in their workplace and share their experiences with colleagues.

Theoretical Foundations and Evolution

Merrill’s Principles of Instruction are grounded in decades of research on design theories and philosophy. David Merrill synthesized insights from behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism to create a model that is both flexible and universally applicable. Unlike some design models that focus on specific content or delivery methods, Merrill’s principles provide a framework that can be adapted to any subject, audience, or technology.

The guidelines align closely with other influential philosophies, such as Gagné’s Nine Events of Instruction and Bloom’s Taxonomy, but they stand out for their emphasis on real problems and active participation. Merrill’s work has influenced countless instructional designers and continues to shape best practices in education and training.

Applying Merrill’s Principles in Instructional Design

Implementing the principles requires thoughtful planning and a learner-centered approach. Here’s how instructional designers can apply each principle in practice:

Designing Problem-Centered Instruction

Start by identifying real problems or tasks that are relevant to your learners. These problems should be complex enough to challenge learners but achievable with the knowledge and skills you plan to teach. Structure your instructions around these problems, using them as the foundation for lessons, activities, and assessments.

Activating Prior Knowledge

Incorporate activities that prompt learners to recall or share their existing knowledge. This could include brainstorming sessions, pre-assessment quizzes, or reflective discussions. The goal is to help learners connect new information to what they already know, making learning more meaningful and memorable.

Demonstrating New Knowledge and Skills

Use a variety of demonstration methods to show learners how to perform tasks or apply concepts. Consider using multimedia, actual scenarios, or expert modeling. Ensure that demonstrations are clear, step-by-step, and directly related to the problems learners will solve.

Facilitating Application and Practice

Provide ample opportunities for learners to practice new skills in a supportive environment. Design exercises, simulations, or projects that mirror realistic challenges. Offer timely feedback to help learners improve and build confidence.

Encouraging Integration and Reflection

Create opportunities for learners to integrate new information into their daily lives. Assign projects that require real-life application, facilitate group discussions, or encourage learners to teach others. Reflection activities, such as journaling or peer feedback, can also help learners internalize what they have learned.

Real-World Examples

To illustrate the power of the principles, let’s consider a few real-world scenarios across different fields:

Example 1: Corporate Training

A company wants to train employees on a new customer relationship management (CRM) system. Instead of simply presenting features and functions, the instructional designer creates scenarios based on common customer interactions. Employees are asked to solve actual problems using the CRM, drawing on their prior experience with similar tools. The trainer demonstrates key tasks, then allows employees to practice in a simulated environment. Finally, employees are encouraged to use the CRM in their daily work and share tips with colleagues.

Example 2: Higher Education

A university course on environmental science is redesigned using Merrill’s Principles of Instruction. Students begin by tackling environmental issues, such as designing a plan to reduce campus waste. The instructor activates prior knowledge by discussing students’ experiences with recycling. Demonstrations include case studies and expert interviews. Students apply their knowledge by developing and presenting waste reduction proposals. Integration is achieved through community projects and peer teaching.

Example 3: Online Courses

An online coding bootcamp uses the principles to teach programming. Learners start with real projects, such as building a personal website. The course activates prior knowledge by reviewing basic computer skills. Instructors demonstrate coding techniques through video tutorials and live coding sessions. Learners practice by completing coding challenges and receive instant feedback. Integration occurs as learners share their projects with the online community and contribute to open-source initiatives.

Benefits of Applying Merrill’s Principles

Merrill’s Principles of Instruction offer several key benefits for designing effective programs and outcomes:

- Enhanced Engagement: By focusing on real problems, learners are more motivated and invested in the process.

- Improved Retention: Activating prior knowledge and providing demonstrations help learners make meaningful connections, leading to better retention.

- Practical Application: Opportunities for practice and incorporation ensure that learners can apply new information and skills practically.

- Adaptability: The guidelines are flexible and can be applied to any subject, audience, or delivery method.

- Evidence-Based: Merrill’s philosophy is grounded in research and have been validated across diverse educational settings.

Challenges and Considerations

While Merrill’s Principles of Instruction provide a powerful framework, implementing them effectively requires careful planning and a deep understanding of learners’ needs. Some challenges include:

- Identifying Authentic Problems: Designing programs around real issues can be time-consuming and may require input from subject matter experts.

- Balancing Demo and Practice: Ensuring that demonstrations are clear and that learners have sufficient opportunities for practice can be challenging, especially in large or diverse groups.

- Facilitating Incorporation: Encouraging learners to integrate new information into their daily lives may require ongoing support and follow-up.

Despite these challenges, the benefits of applying the principles far outweigh the difficulties. With thoughtful planning and a commitment to learner-centered instruction, educators and designers can create transformative experiences.

Want to bring Merrill’s Principles to life in your organization? Our instructional design services help you build problem-centered, application-focused learning that delivers real results. Reach out to TimelyText to get started.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

I’m a storyteller!

Exactly how I’ve told stories has changed through the years, going from writing college basketball analysis in the pages of a newspaper to now, telling the stories of the people of TimelyText. Nowadays, that means helping a talented technical writer land a new gig by laying out their skills, or even a quick blog post about a neat project one of our instructional designers is finishing in pharma.